Skagit River Journal

Subscribers Edition Stories & Photos

|

This is a page from our Subscribers Edition. Our free site remains free. How to subscribe to our separate online magazine or donate to our project |

Skagit River JournalSubscribers Edition Stories & Photos |

|

|

|

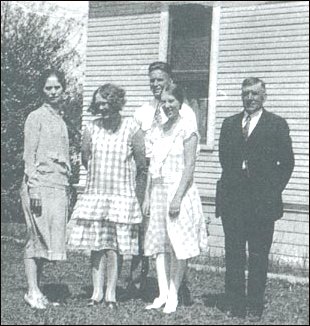

The Newberg family at their Utopia farm in 1917. From left to right: Anna, mother, age 44; Mary, 16, Gladys, 19; Charley, father, 51; Bill, age 7; rabbit, age 1; dog, age 2, in the 1915 Model T for which Charley traded a horse, who knew his way home. |

When I was growing up in the Utopia district east of Sedro-Woolley in the late 1950s, one year all of Utopia buzzed with the news that Bill Newberg, the most famous man to grow up in that bucolic country district, was being honored for his promotion to president of Dodge Motors in Detroit. We used to ride our bikes by his old farm on the Skiyou/Hoehn road and wonder how anyone from here could become such a famous corporate executive. We got our answer in 1955 when he introduced a blaze of color to Dodge cars that set them apart from their bland ancestors.

|

Whenever a chinook wind swept up the mountain slopes we knew the melting snow would bring heavy floods. One of my jobs was to get the cows out of the pasture to high land. Sometimes the river rose a foot an hour. Across the stream we had a bridge anchored by cable. Once the cows were cut off from the bridge by rising water I faced a tough problem. I felt like a marine cowboy trying to round up the herd. Finally I got an old cow named Lucy headed onto the bridge and fortunately the others followed, crossing safely and wading through rushing water on the other side. We had a raft for emergency use but sometimes the water was so deep you couldn't even pole the raft. Fish were plentiful when the floods receded. They'd be trapped in holes that that had been made when stumps were blasted out.Fifteen-year-old Bill got a harsh lesson about the right way and wrong way of laying shakes on the roof of their new barn. A neighbor known as Big Knute Anderson saw Bill nailing them wrong and gave him the worst chewing-out ever. The youngster learned the proper way and worked so hard as they completed the barn that he fell asleep when the neighbors threw a party and missed it entirely.

|

|

|

It's true that automobile production and automobile designing are 'out for the duration,' but just the same the design and type of a new car to be built after the war is taking place in engineers' minds. Don't expect much of a car the first year or so after the war. They won't have to be sensational — the public will buy almost anything. But three or four years after the war ends — then look for an automobile the like of which we've never dreamed about.In January 1944, six months ahead of schedule, the Dodge was producing the 2,200-horsepower Wright engines full time. By war's end, Chicago plant manufactured 18,413 of the engines and in June that year the B-29s began pounding the Japanese mainland with them. By war's end in 1945, Bill had proven his ability to direct the engineering of a vast project, but he longed to get back to Detroit in time to prepare for the demand for new cars that he knew was just around the corner. Chrysler Corporation had different plans for him, however; they assigned him to another branch of the company, Chrysler Airtemp division at Dayton, Ohio, which was mired in red ink as a result of the same wartime restrictions that impeded production of cars. Company executives realized that he was a problem solver and after two years of learning the processes of heating refrigeration and air conditioning manufacturing, he was appointed president of Airtemp in 1947. Under his leadership the subsidiary's business tripled by 1950.

|

[Bill Newberg explains that] "nowhere is there more misunderstanding that in the evaluation of the amount of the money that can be saved through automation. . . . Many kinds of automation might be rejected because they do not promise a net reduction in manpower, but they might prove most profitable if considered from the standpoint of safety, savings in floor space, improvement in quality or increased production.By the time Bill's parents visited him at the wartime Chicago plant, they had sold the Utopia farm and moved to Sedro-Woolley in 1942. Charley Newberg died here on Jan. 12, 1946. Anna Newberg continued to live in Sedro-Woolley until her death on Feb. 13, 1956, at age 81. After retiring from Chrysler in the early 1960s, Bill was an officer of the Detroit Bank of Trust and held various corporate positions. The family moved to Reno, Nevada, in 1974, where Bill was very active in real estate for the next 20 years. Bill and Dorothy moved this year to a retirement center. Dorothy fell in 1998 and Bill has been her loving caregiver for the past four years. The Newbergs have four children. Judy Bracken has a master's degree in architecture from MIT and is an environmental lawyer. Robert Newberg lives in Reno, where he operates an auto parts warehouse. James Newberg also lives in Reno, where he is a financial executive for international Game Technology, the largest slot machine manufacturer in the world. Bill Jr. is controller and chief financial officer of an electrical distributing company that has offices in both Reno and Las Vegas.

More important than space saving is the saving of life and limbs, for automation is the greatest boon to industrial safety in the history of the industrial age. The approach to automation strictly from the standpoint of reduction in productive labor is false economy. There is no doubt that some operations in manpower can be saved through the use of automated equipment. The overall effect of automation, however, probably will be to increase total employment.

With increasing use of automation will come an increase in the number of persons in the category most of us consider nonproductive labor; that is, maintenance personnel and technical specialist who will concern themselves with the never-ending task of improving and refining mechanical processes."

And Bill Newberg is determined to abandon equipment and methods approaching obsolescence — just as determined as he was to leave behind the milking pail on the Skagit farm and donkey engine in the woods.

|

Please report any broken links or files that do not open and we will send you the correct link. Thank you. |

|

Oliver Hammer Clothes Shop at 817 Metcalf street in downtown Sedro-Woolley, 82 years Bus Jungquist Furniture at 829 Metcalf street in downtown Sedro-Woolley, 36 years Peace and quiet at the Alpine RV Park, just north of Marblemount on Hwy 20 Park your RV or pitch a tent by the Skagit river, just a short driver from Winthrop or Sedro-Woolley College Way Antique Mall, 1601 E. College Way, Mount Vernon, WA 98273, (360) 848-0807 Where you will find wonderful examples of Skagit county's past, seven days a week North Cascade Ford, formerly Vern Sims Ford Ranch, West Ferry street and Crossroads/Highway 20 either on the Sedro-Woolley page or directly at www.northcascadeford.com DelNagro Masonry Brick, block, stone — See our work at the new Hammer Heritage Square See our website www.4bricklayers.com 33 years experience — 15 years as a bonded, licensed contractor in the valley Free estimates, reference, member of Sedro-Woolley Chamber  (360) 856-0101 (360) 856-0101 |

|

|

|

|

|

View Our Guestbook |

|

|

Mail copies/documents to street address: Skagit River Journal, 810 Central Ave., Sedro-Woolley, WA, 98284. |