James Alexander Patterson's

family connection to impeached

President Andrew Johnson

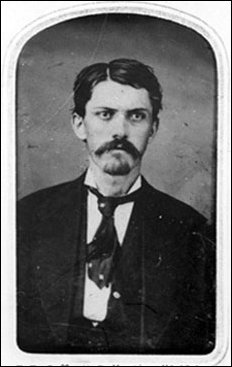

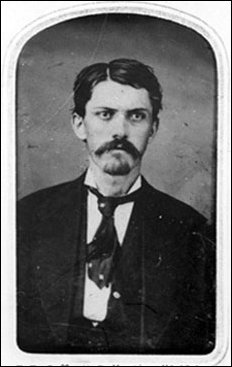

| James A. Patterson, ourtesy of the Percival R. Jeffcott collection, Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, Fairhaven

|

|

In her book, Ideal Home, Phoebe Goodell Judson made a connection between Patterson and the impeached 17th U.S. president, Andrew Johnson, "Two of his brothers were senators, and a niece presided as first lady of the White House, as the wife of Andrew Johnson." She went on to explain that Johnson was orphaned as a child, then became a street urchin because his mother was reduced to poverty, and was educated by his wife, whom Phoebe identified as Patterson's niece. Although she got the part mainly right about Johnson's childhood, she was confused about his wife.

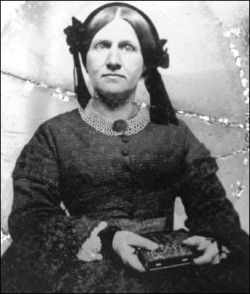

We are always interested in connections like this one, so we will briefly explain and correct the record. Johnson was born in North Carolina and his father died when he was three. After he and his mother were mired in poverty while he was a child, he apprenticed to a tailor at age ten and was eventually able to support his mother. After working at several tailor shops, a tailor in Greeneville, Tennessee hired him, and he moved his mother and stepfather there to live with him. He also soon met Eliza McCardle, the daughter of a shoemaker, and they married in 1827, after which the couple had five children in the years up to 1852. Johnson proved to be a very able debater and soon rose through the local and state political ranks as a Whig and champion of the common man. He served five terms as a U.S. representative from Tennessee, returned to be elected governor for a term and then was elected to the U.S. Senate. While there he gained national attention as the father of the Homestead Act, which was especially important to pioneers in the Pacific Northwest. In 1864, Democrat Johnson was tapped by President Abraham Lincoln to replace Vice President Hannibal in his second term. Eliza Johnson was ill and avoided any public appearances after Johnson assumed the presidency following Lincoln's assassination.

That is when the Patterson family came into the White House picture. Back in Tennessee, the Johnsons' eldest child Martha married David Trotter Patterson in 1855. Tennessee was the only southern state to ratify the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, so the state was readmittted to the Union in 1866 and Patterson was elected U.S. Senator, succeeding his father-in-law. James A. Patterson was Senator Patterson's brother, so the First Lady Phoebe referred to was certainly his niece, and she did act as First Lady, but only as a replacement because her mother was so ill. Martha Johnson Patterson and her married sister both took turns representing her mother at public functions, a challenging role, indeed, when Johnson was impeached by the House but then escaped conviction by the Senate by only one vote. [You can also read the other connection between a Northwest family and the impeachment: the Ewings of Mount Vernon.] When we interviewed Reg Rittenberg, we learned that James may have married back in Tennessee but was either widowed or divorced before he moved west. Regardless of whether James was married, Reg learned from a Patterson relative that James fathered a daughter and that David and Martha Patterson raised her after he moved west.

|

See this

See this